My experience as the middle child in my family has taught me to accept all of my quirks that set me apart from my brothers, to embrace my individuality and to stand on my own two feet.

Ever since I was little, as the middle child in my family, I have always felt like somewhat of an alien in my house – the oddball misfit. From the outset, the stark differences between my brothers and I were painfully obvious – where they were sporty and steered by scientific fact, I was geared towards using my imagination and natural creativity. As a child, I never felt as though I belonged to the family. I would joke I must’ve been swapped at birth.

Both of my brothers favour maths and science over humanities and played soccer like it was their divine birthright from an early age. Me? I saw a maths equation in prep and thought, “Nah this is some bullshit,” and never looked back. Soccer on the other hand, is unfortunately not the meaning of my life. I wanted to read and write during school hours, then dance and act after classes.

Being the eldest, middle or youngest child in a family is said to affect personality or tends to box siblings into certain perceived identities. The eldest tends to carry the weight of the world on their shoulders, the youngest notoriously gets the most attention and the middle child is just sort of “the other one”.

Somehow my parents got landed with me – a hyperactive, loud and outgoing daughter, with an overactive imagination, more interested in memorising the lyrics to every Taylor Swift song or reading Harry Potter for the ninety-seventh time than sport or maths. I wanted to spend my time on arts and crafts, writing stories on scrap pieces of paper and reading with my torch under the covers after lights out. Yes, I know I was such a rebel.

I was the strange middle child who thought soccer was the most overdramatic and ridiculous sport on the planet and questioned why maths was even taught in the first place.

Clearly, there was always something fundamentally different about what I enjoyed and valued compared with my brothers.

Teachers at my high school always acted as though my older brother was God’s gift to the planet, a maths-science gun ready to save the world with his genius. I’d arrive to maths class every year with teaching staff who’d hear my surname, and their eyes would light up with joy, expecting another prodigy. Instead, ten minutes later, they’d realise I was not a Ferrari of a student, I was a rickety old tow truck whose eyes would glaze over at the sight of maths equations.

I was more interested in drawing hearts in the margins or egging on the teaching staff with philosophical questions like, “but why?” or, “how do we know that maths is even real?”

I was more interested in drawing hearts in the margins or egging on the teaching staff with philosophical questions like, “but why?” or, “how do we know that maths is even real?”

I would ask myself why are there letters with numbers, how does this apply to the world and most importantly, why should I care? It sounded like a load of waffle to my high school self. Maths wasn’t something at which I excelled, unlike both of my brothers.

And I also couldn’t comprehend the fuss about soccer. Players run around a pitch for ninety horrifyingly dull minutes, nobody scores whatsoever, and the team acts as if every game is a matter of life or death. I wish I was kidding.

I also somehow lacked the sense of direction that both of my brothers magically possessed. They knew what they wanted to do and who they wanted to be. I had absolutely no idea what I was supposed to do with my interests and odd skill set.

I liked to read stories, shout lyrics and act in school plays. I didn’t know where my life was going to take me. I was the odd one out.

Outsiders to the family noticed it too. Family friends would ask why I wasn’t “like” my brothers, or they’d address me as the “little sister”. They saw me as adjacent to my brothers, rather than a person on my own. They wouldn’t ask how I was doing; they’d ask how my brothers were doing.

Some would simply forget I existed in the first place. I’d hear “oh wait there’s a third sibling?” all the time. I would think to myself, yes, Jennifer you and I have met on several occasions, you just didn’t happen to notice that I too am a fully-fledged and functioning member of society. Also, eat my shorts.

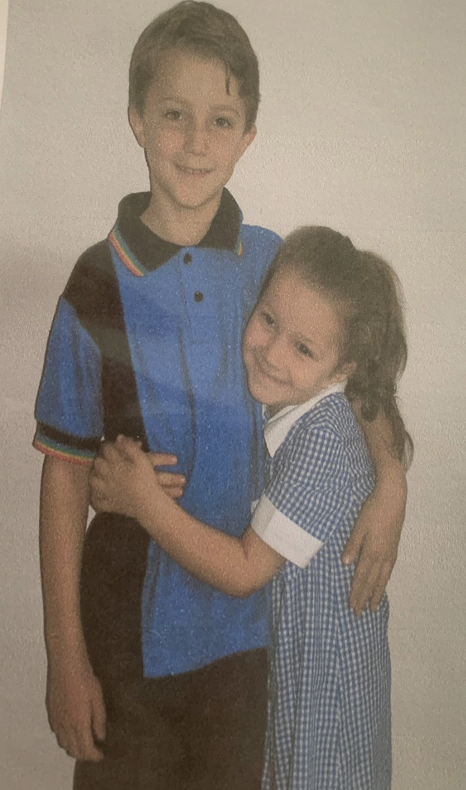

Don’t get me wrong, I’m quite close with both of my brothers, they aren’t monsters or anything. They’re the best! It’s just that sometimes I’d feel as though I was chocolate, and they were both pasta. Both foods are great in their own right, they’re just quite different and you wouldn’t exactly put them together.

Sometimes, I would let it get to me. I would get so worked up at everyone. How could they not see that I was there too? I mean sure I wasn’t like my brothers in some respects, but I knew I was just as valid and valuable. I just wanted other people to recognise it!

When I was in Year 11, one of my teachers who was in the crowd with me while my older brother was receiving yet another award turned to me and said, “Don’t worry, your time will come!”

Such a small phrase was a massive turning point for me. In true middle child fashion, I was unsurprisingly morbidly offended and went home to cry in my bedroom. I was 16 years old and coming of age myself. I was excelling in other areas like English and theatre, but somehow still being brought to a lower level than my brother. I was still being cornered into the mould of the somehow lesser middle child.

I didn’t want to wait around until my brother stopped being fabulous. I believed that my time was now.

I had spent years thinking others would only ever see me as a sister rather than a person myself and I was struggling with the fact that I didn’t know how to break away from my brothers and stand on my own. It was at this point that all the stars and planets aligned, the universe opened, and I realised that all it took was a change in my mentality.

I had to ignore outsider opinion or comments and I had to accept that I was not the same as my brothers and use those differences to my advantage.

I focused my studies on English. The best part of my week was when I would get to write my essays. I loved it! Now, it was my brothers turn not to understand me. I could do it all day. It wasn’t anything like the rigidity and one right answer structure of maths. It was creative, opinionative and fun. All of those years of reading, music listening, lyric bellowing and drama pieces pointed to a love for both words and the stories they tell.

I had finally realised that this was my passion. As the different middle child. I was the odd one out, and that was okay!

I had finally realised that this was my passion. As the different middle child. I was the odd one out, and that was okay!

I am now almost 21 and have turned my love for humanities into an arts and law degree, majoring in literary studies. My family still watches soccer every Saturday and I do begrudgingly join them now. If you can’t beat them, join them. My brothers still harp on about maths and science and I still think it’s the strangest thing in the world and that’s also okay! They don’t understand some of my passions and I certainly don’t understand some of theirs.

I myself still don’t always know what I am doing with my life. I still have moments where I feel like a coco pop in a family of rice bubbles. I still don’t always have the answer.

Maybe I’ll become a lawyer or a publisher or a writer or choose from the endless options humanities has to offer. Or maybe I’ll move to Hogwarts to become a witch. Or maybe I’ll be a unicorn when I grow up.

I mean, who knows what I’ll do. I am the middle child after all.