Every January, a line is drawn between those who celebrate Australia Day and those who protest it, raising important questions about our national identity and history.

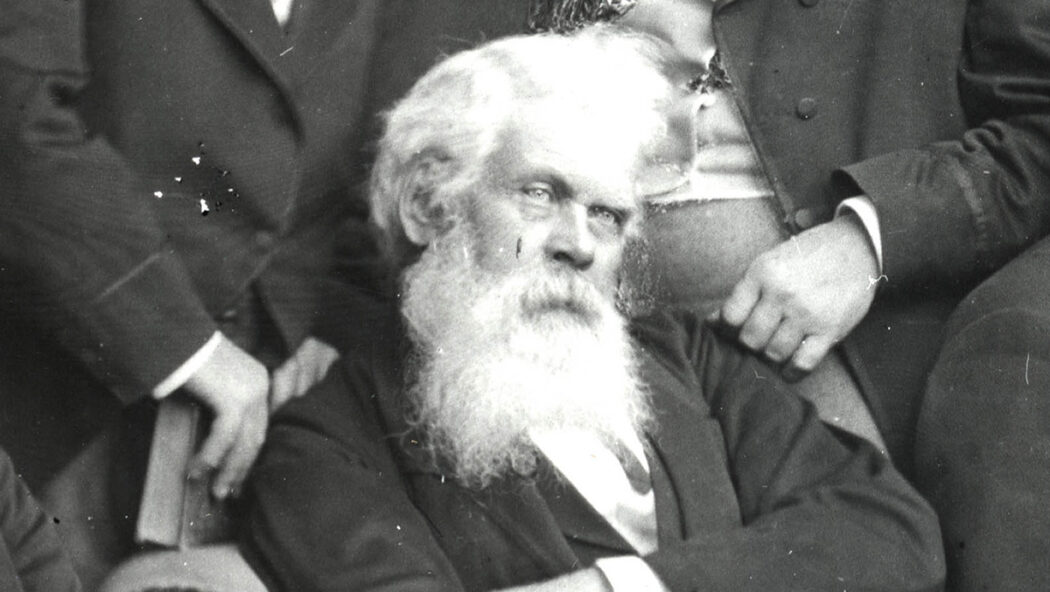

In 1888, when then-premier of New South Wales, Sir Henry Parkes, was asked whether a centenary celebration was being planned for Indigenous Australians alongside the settlers’ celebration he responded, “And remind them we have robbed them?”.

Since that time, a debate has been ongoing: should Australia Day be celebrated or scorned?

For those who celebrate the day, it’s associated with a public holiday, fireworks, barbecues, and pool parties. It’s a celebration of Australianness. Those that protest it call it Invasion Day, Survival Day, or the Day of Mourning to reflect our brutal colonial past.

The origins of Australia Day: the non-Indigenous perspective.

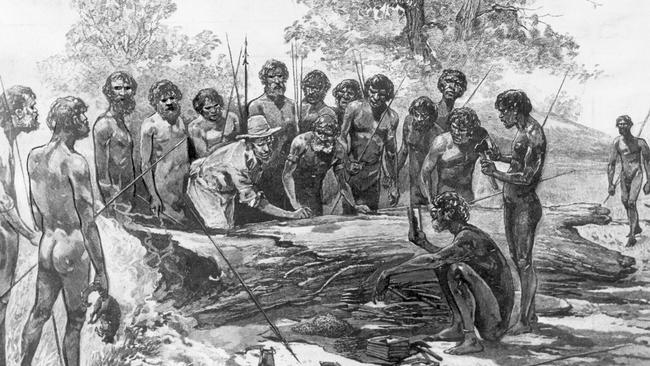

On 26 January 1788, Captain Arthur Phillip, captain of the First Fleet of convict ships sent from Great Britain, raised the British flag in Sydney Cove to signal the creation of the colony of New South Wales.

As Australia was being explored, John Batman, one of the pioneers in the founding of Victoria, settled at Port Phillip. He attempted to buy the land from the Indigenous people living there by entering a treaty with them.

Batman’s treaty was overridden by the NSW Governor, Sir Richard Bourke, who issued a Proclamation on 10 October 1835 that Australia was terra nullius – nobody’s land – even though Indigenous people had lived on the continent for at least 65,000 years.

Celebrating NSW’s founding 30 years later in 1818, the Governor gave all government employees the day off. Initially, only NSW celebrated the day of colonisation known variously as ‘First Landing Day’, ‘Anniversary Day’ or ‘Foundation Day’.

Other colonies celebrated their own beginnings in their own ways. In Tasmania – known then as Van Dieman’s Land – Regatta Day in early December acknowledged both the landing of Abel Tasman in 1642 and the state’s separation from NSW. In Western Australia, Foundation Day on June 1 celebrated the arrival of white settlers in 1829. South Australia held their Proclamation Day on December 28.

In 1838, 50 years after the First Fleet’s arrival, Foundation Day was declared Australia’s first public holiday in NSW.

Empire Day was introduced on 24 May 1905 – Queen Victoria’s birthday – to celebrate ties between Australia and England. On July 30, 1915, an Australia Day was held to help raise funds for World War I.

By 1935, January 26 was recognised as Australia Day in all states except NSW, where it was called Anniversary Day.

Agreement between Commonwealth and state governments to call 26 January ‘Australia Day’ across the country came in 1946 and, since 1994, Australia Day has been a national public holiday.

The National Australia Day Council (NADC), founded in 1979, views Australia Day as a celebration of “our nation, its achievements and most of all, its people”. It’s on Australia Day that new citizens are welcomed, and inspirational Australians honoured.

Australia Day: the Indigenous perspective.

On 26 January 1938, Australia celebrated the 150th anniversary of the landing of the First Fleet. As part of the celebrations, Indigenous peoples were forced to participate in a re-enactment of the landing.

As part of the celebrations, Indigenous peoples were forced to participate in a re-enactment of the landing.

Twenty-five Indigenous men from Menindee in western NSW were gathered up, placed onto a mission truck, and brought into Sydney. They were told that if they didn’t participate, their families would starve. To further ensure their participation, the men were locked in the Redfern Police Barracks until the re-enactment took place and, on that day, were chased by British soldiers with bayonets.

The re-enactments were only discontinued in 1988.

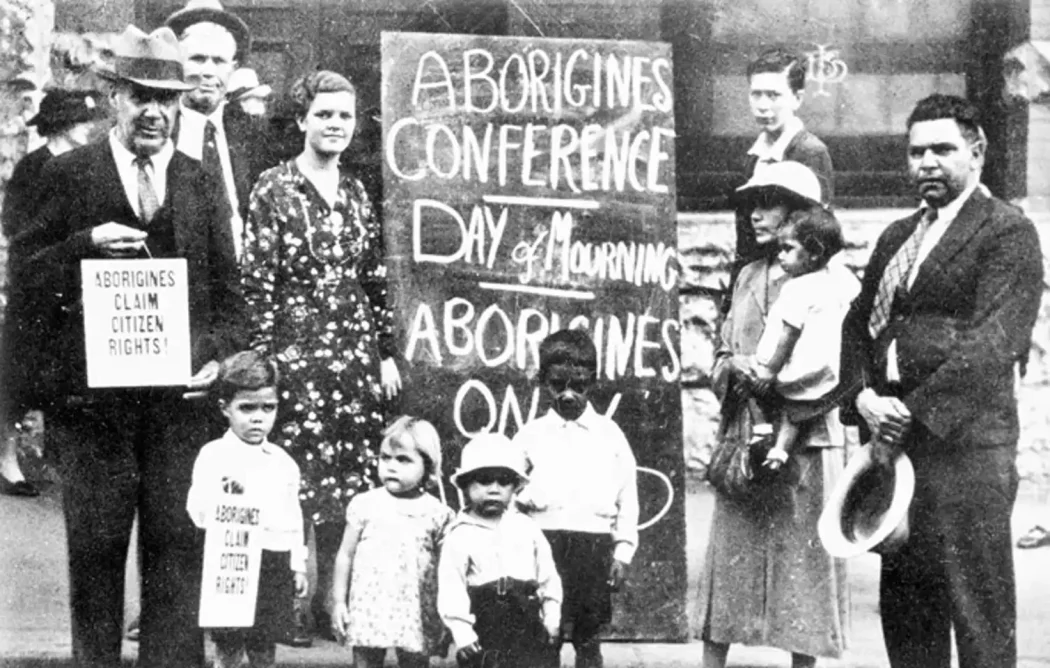

In response to the sesquicentennial celebrations, a group of over 100 Indigenous people protested the violence, dispossession, and discrimination that Indigenous people had experienced since 1788. They called it the ‘Day of Mourning’ and argued for citizenship, full rights, and better access to education for Indigenous peoples.

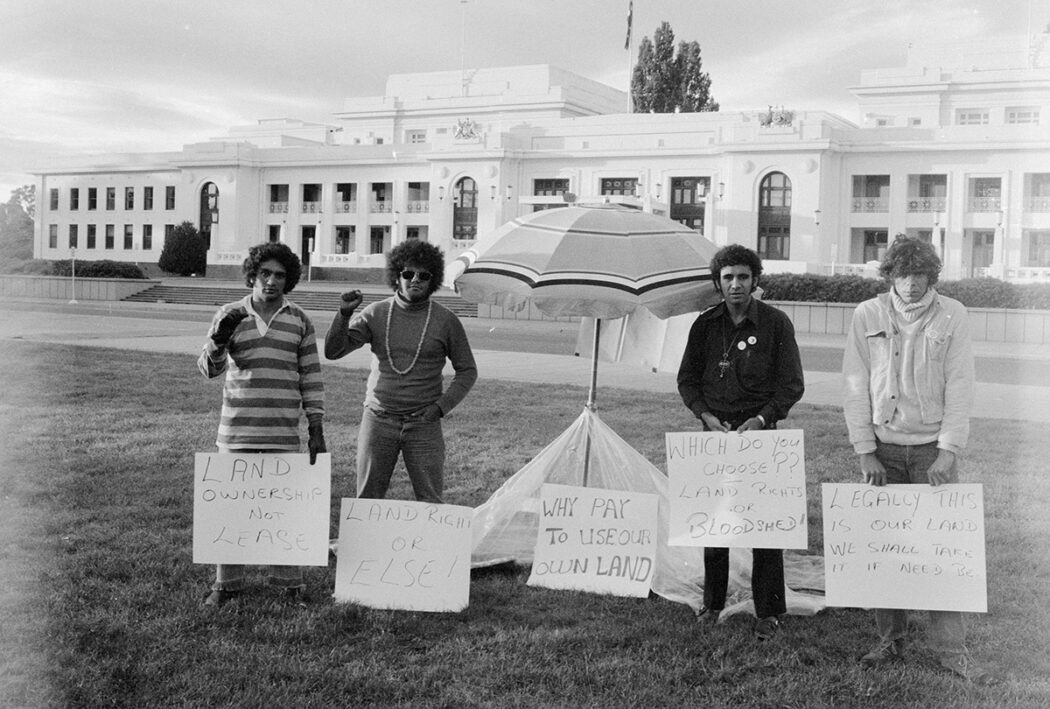

On Australia Day 1972, four Indigenous men set up a beach umbrella opposite Parliament House, Canberra, in protest of the government’s alienation of Indigenous peoples. Thus, the Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established.

In 1988 – on the two-hundredth anniversary – when the country collectively agreed to celebrate Australia Day on 26 January rather than with a long weekend, Indigenous peoples renamed the day ‘Invasion Day’.

At the same time as Sydney’s bicentenary celebrations, more than 40,000 Indigenous people and their supporters staged what was the biggest march ever seen in Sydney.

The 1988 protest focused national and international attention to Australia’s ongoing history of colonisation and aimed to educate people.

Carried out in the same spirit as the 1938 Day of Mourning protest, the 1988 protest focused national and international attention to Australia’s ongoing history of colonisation and aimed to educate people about the poor conditions of Indigenous health, education, and welfare.

Why is Australia Day offensive to Indigenous peoples?

Aboriginal activist and lawyer, Palawa-Pinterrairer man Michael Mansell has accused Australia of exhibiting a double standard when it comes to Australia Day. While Australian soldiers who died at Gallipoli are revered with a public holiday and the erection of monuments, there are no monuments or holidays for the Indigenous people who fell victim to white settlers.

Mansell points out that Australia is the only country that celebrates its national day based on the arrival of Europeans.

Australia is the only country that celebrates its national day based on the arrival of Europeans.

Australia did not become a nation until 1901 when the six, then-separate British colonies united to form the Commonwealth of Australia. Prior to the implementation of Australia’s Constitution, Indigenous peoples were not counted as citizens and, therefore, denied the vote.

It is argued that an official national day is meant to celebrate the beginning of nationhood which, in Australia’s case, is 1901. Therefore, for Indigenous peoples, the only significance of 26 January 1788 is that it was when the British set foot on, and took over, Indigenous land.

Gamillaroi and Torres Strait Islander woman, playwright/actor Nakkiah Lui, views Australia Day as a day of mourning for Indigenous peoples: mourning for the declaration of Australia as terra nullius; for those who were massacred; for those who were removed from their lands and oppressed; for those whose children were stolen. Lui also mourns the effects of genocide and colonisation that persist today.

In 2019, Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) data showed 46% of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples had at least one chronic condition that posed a significant health problem. The ABS also reports that the life expectancy for Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander males is more than eight years less than non-Indigenous males. For Indigenous females it is around eight years less.

For these reasons, many Indigenous peoples view Australia Day as painful, marking the beginning of colonisation. They have been protesting 26 January for a long time but, in recent years, more people – including local governments and community organisations – have joined the #changethedate movement.

Changing the date: will it change anything?

Calls to change the date of Australia Day have grown over the last five years. Much of the debate is drawn along generational lines.

In 2019, Australian National University’s Social Research Centre (SRC) found that 58% of Millennials and 47% of Gen Z were far less supportive of celebrating January 26 compared with 73% of Gen X and 80% of Baby Boomers who wanted to keep the date. The Silent Generation – those born before Baby Boomers – were almost unanimous in their support of retaining the date of January 26 (90%).

These figures demonstrate movement toward changing the date. Importantly, younger generations are more likely to be aware of Indigenous issues as there is more inclusive history taught in schools.

ABC’s Australia Talks National Survey 2021 found that a majority – 55% – of Australians are for changing the date “given the historical significance of that date for Indigenous people”. This was an increase of 12 percent since the last survey in 2019.

However, these results do not accord with a national poll conducted by Ipsos in January 2021 which found that half of Australians (48%) did not want the date changed.

Gamillaroi man Luke Pearson warns supporters of #changethedate not to forget that it is not just the date on which Australia Day is celebrated that is the problem; it is what is being celebrated on that date.

For Pearson, more needs to change before the date is changed. He considers changing the date to be the final item on a list that includes addressing higher incarceration rates for Indigenous peoples, health and education issues, housing, and unemployment. These things need to be dealt with first.

Changing the date does not change what happened on it.

The negative feelings Indigenous people have towards the date are not going to go away simply because Australia Day is moved.

Some, including some Indigenous people, suggest that the date should be retained, used as a time to reflect on our past and its injustices. That the day does not have to be either Australia Day or Invasion Day, it can be both: a recognition of the damage done by colonisation and a celebration of what a great country Australia is.

What should the new date be?

There are a number of dates suggested that still celebrate Australia and Australianness, just not on a day that is painful for many Indigenous people. Here are some possibilities:

- 1 January: the day Australia came into being on the Federation of Australia, 1 January 1901.

- 18 January: the day the Supply, one of the first three First Fleet ships to reach Botany Bay, arrived.

- 13 February: the date, in 2018, the government apologised to the Stolen Generations.

- 2 March: when in 1986 Prime Minister Bob Hawke and Queen Elizabeth signed the Australia Act 1986, making Australia a fully independent, sovereign nation (it came into effect the following day).

- 19 April: the date in 1984 when ‘Advance Australia Fair’ was proclaimed the National Anthem.

- 9 May: the date in 1901 when the first meeting of the Commonwealth parliament took place and the day on which Australia became a self-governing, independent commonwealth.

- 27 May: the date of the 1967 referendum that removed constitutional clauses that discriminated against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders (‘Reconciliation Day’).

- 3 June: the day the High Court overturned the doctrine of terra nullius and acknowledged native land rights (‘Mabo Day’).

- 9 July: the date Queen Victoria gave her acceptance to the Constitution of Australia in 1900.

- 30 July: the date of the first Australia Day in 1915.

Do we celebrate the old or the new? Or both?

Ultimately, it comes down what is more important: the 65,000-plus years of Indigenous occupation before 1788, or the 230-odd years since. Do we celebrate the old or the new? Or both?

The question ‘Do we change the date of Australia Day?’ involves the weighing up of complex social issues. It a question that, unfortunately, is not easily answered.