The story of how my drinking caused my life to spiral into chaos and my journey back through sobriety.

“My name is Paul, and I am an alcoholic.”

I don’t remember much about my first Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) meeting. I put it down to being so mentally and physically broken that all I have is a vague recollection: a group of people sitting in a large circle, lit by candlelight. What I distinctly remember, though, is hearing those present speak their truth and knowing, immediately, that I was in the right place.

I was a successful lawyer, well-respected by clients and peers alike. Work was my life. It was also, in retrospect, the environment in which I was able to best practise my alcoholism. I just enjoyed a drink, I can’t be an alcoholic, I thought. Alcoholics were homeless and unemployed, drank first thing in the morning out of brown paper bags. I was none of those things, so I kept drinking. And drinking. It took me about fifteen years to get to that first meeting, at the age of 41.

I can’t pinpoint exactly when my drinking changed from social to problematic. Drinking socially became drinking on weekends became drinking a few days during the week became a daily habit. I drank to celebrate, and I drank to commiserate. My drinking had started out fine – fun, even – but, after polishing off an entire wine rack of Tasmanian reds in a week, I wondered if I had a drinking problem.

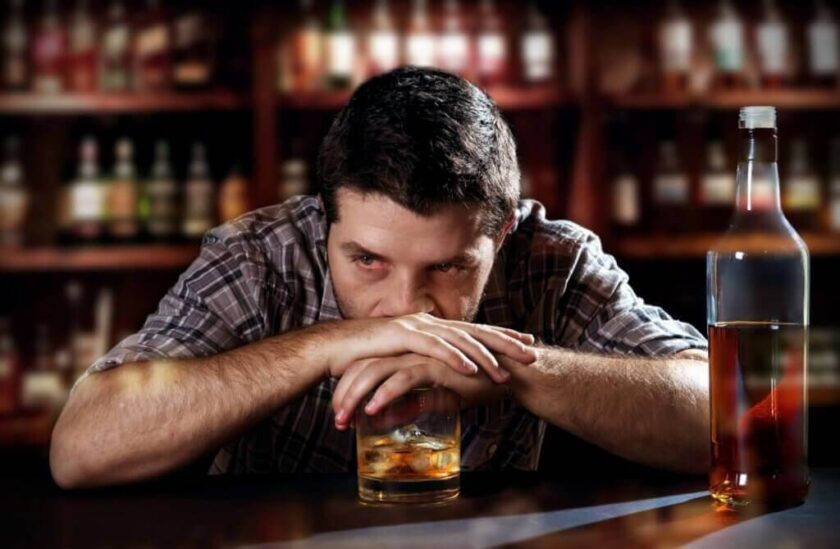

The last few years were the worst. I counted the hours, then the minutes, until I could drink. I craved it, needed it. I continued to work but took more and more sick days. I left work earlier and earlier, going home via the bottle shop where I got into bed and started drinking. I rarely ate. I was drinking two litres of cask wine a day out of a blue plastic wine ‘glass’ because I had broken all the glass ones. I was dogged by a constant and painful obsession: did I have enough alcohol to get me and keep me drunk?

I was drinking two litres of cask wine a day out of a blue plastic wine ‘glass’ because I had broken all the glass ones.

I regularly cracked ribs falling off chairs, was covered in mysterious bruises. I started having blackouts, unable to remember things I’d done or said. I later learned they were caused by drinking too much too quickly, impairing judgment, coordination, and memory. Because of the blackouts, my first morning ritual was to check my phone to see what nasty things I’d texted to friends, trying to piece together the events of the night before. I’d apologised so much that “I’m sorry” no longer meant anything. My second morning ritual was vomiting and diarrhoea. And I kept drinking.

My rage grew exponentially. Plates and cups were broken, cutlery thrown, computer keyboards smashed. My dogs actively avoided drunk me, terrified of my yelling. I cut people off, including my partner and family, retreating into isolation to drink the way I wanted to. Seeing the way I drank, my closest friend – one of the few I still had – told me she knew someone who had stopped drinking by going to AA and suggested I do the same. I told her to “Fuck off”. I still didn’t consider myself an alcoholic despite my unmanageable life. Or maybe, somewhere in the sensible part of my brain, I did.

I had tried to stop or, at least, reduce my drinking in the years before I entered Alcoholics Anonymous. I saw doctors, psychologists, and psychiatrists and lied to all of them about how much I was drinking. I was prescribed drugs to reduce alcohol cravings and washed them down with booze. I read self-help books, books on spirituality. I gave Buddhism a crack. I switched red wine for white and clear spirits for coloured. Going days, sometimes weeks, without drinking, I relied on a willpower that was so fragile it was easily broken watching someone on television sip a martini. None of these methods curbed my drinking. It took hitting what is referred to in AA as ‘rock bottom’ for me to make a change.

My rock bottom involved me, in a blackout, assaulting a taxi driver. I ended up with a broken wrist, the clear loser in that encounter; the taxi driver was unharmed. Cut to me laying on an emergency department trolley, my right forearm plastered, in a great deal of physical and emotional pain. It was what I needed. I reflected on where my life was headed, without the fog of alcohol. Terrified I would be charged with assault, which might mean the end of my law career, my best friend’s words – “you need to go to AA” – circled around in my head. It was the only viable option I had left; I’d tried everything else. It was either jail, a slow death, or Alcoholics Anonymous. I left hospital resolved to give AA a try for a month.

It was either jail, a slow death, or Alcoholics Anonymous.

My understanding of AA was minimal, informed by media portrayals of alcoholics. I searched online for a local meeting and dragged my partner along for support, not knowing what to expect. Although I sat in the corner, not speaking, I felt instantly understood. Importantly, I realised that I was not alone in this, I was not the only person in the world with this problem. The next day I went to another meeting, then another, and another. I did 90 meetings in 90 days as suggested. I learned that alcoholism is a disease that can be treated by attending meetings, getting a sponsor, and working through the twelve steps that underpin the AA program.

And I didn’t drink. One day at a time, I clocked up a week of sobriety, then a month, then six months. I kept going back. I started feeling more human. My obsession with alcohol left me after three months. For the first time in a very long time, I didn’t argue; I listened. What I heard was versions of my story voiced by people from all backgrounds. The myth of the stereotypical alcoholic I had, for years, used to justify my drinking was exploded. Alcoholism can affect anyone, regardless of age, cultural background, or socioeconomic status.

Socialising with people outside of AA was tricky to navigate at first. Australia is renowned for being a nation of drinkers. The National Drug Household Survey reported that 77% of Australians over the age of 14 drank in 2018, with 29% using alcohol to a harmful extent. So, it is unsurprising that I was often asked, “Why aren’t you drinking?” My response – “I’m doing it for my health” – satisfied most people.

Persistent questioners were met with, “You wouldn’t like me when I’m drunk” or “I’ve had enough booze to last me a lifetime.” I directed those who wondered out loud whether they might be an alcoholic to Alcoholics Anonymous’ quiz, they had to arrive at that decision themselves.

AA is a spiritual program but let me correct a common misconception. It is not a religious cult. Yes, God is an integral part of Alcoholics Anonymous, but it is a god of my understanding. Growing up areligious, the idea of a DIY god, whether that be a burly, white-bearded man who lives in the sky or the beauty of nature, fit perfectly with my concept of spirituality. I readily put my faith in a power greater than myself, someone or something that could guide me; a spiritual buddy that took the focus off me and my ego.

For me, Alcoholic Anonymous worked. I’m not sure how, and I don’t care. Over time, I came to understand what drove my behaviour, why I reacted poorly in certain situations. Alcohol had been my anaesthetic, an escape from myself and a way of avoiding the feelings that are an inevitable part of life.

AA gave me a blueprint for living and the tools to address feelings in a non-self-destructive way. Now, I am honest with myself and others. I’ve made amends to people I had hurt and repaired relationships with family and friends. I am reliable, able to show up for people instead of making plans and then ditching them at the last minute.

Soon, I will celebrate eight years of sobriety. I still go to meetings a few times a week, where the stories of newcomers, as broken as I was when I first entered AA, remind me of where I was and where I am now. I regularly speak to my sponsor and other sober alcoholics. Four years ago, I paid off a $40,000 credit card debt I’d racked up during my drinking. Three years ago, I married my partner of 20 years who, by some miracle, had stuck by me despite often bearing the brunt of my alcohol-fuelled rage. Being sober does not mean living a boring life. I have done things in sobriety I never dreamed of doing while I was drinking. Today I can laugh – really laugh – again.

Being sober does not mean living a boring life. I have done things in sobriety I never dreamed of doing while I was drinking.

Alcoholics Anonymous can stop you drinking and give you tools for living but it is not a cure-all. I have had to seek help outside of AA for mental illness. But what AA has given me, and continues to give me, is a great deal of serenity and a wonderful support system. I am now the best version of myself.

Don’t get me wrong, it hasn’t always been rainbows and unicorns, but neither is life. I have lost friends and family during my sobriety; I have been laid off from jobs and suffered financial hardship. The difference is that now I am present, can contribute, participate, help and support others and myself without turning to alcohol.

Renowned countercultural writer Kurt Vonnegut, not an alcoholic himself, once said that Alcoholics Anonymous was America’s greatest gift to the world, and I must agree.