We’re all familiar with PMS.

80% of women experience some form of physical or emotional symptoms just before their period starts. However, around 5-10% of women, experience what is known as Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder or PMDD – a mood disorder that requires treatment to alleviate symptoms.

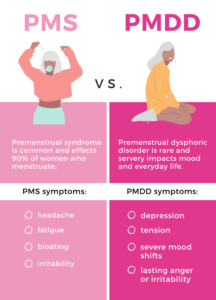

For these women, the week before their period marks the onset of symptoms so severe that getting on with daily life is impossible. These tangibly different yet similarly presenting conditions cause PMDD to be often confused for ‘severe PMS’. But, where PMS is uncomfortable or annoying, PMDD is debilitating.

PMDD was included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mood Disorders as a ‘depressive disorder’ – just six years ago. Since then, the existence of the condition has been gaining awareness amongst women and the medical community. However, that PMDD is not widely spoken about or recognised means that more conversations and research into the condition are needed.

PMDD was included in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mood Disorders as a ‘depressive disorder’ – just six years ago. Since then, the existence of the condition has been gaining awareness amongst women and the medical community. However, that PMDD is not widely spoken about or recognised means that more conversations and research into the condition are needed.

PMDD often being described as ‘PMS on steroids‘ or ‘severe PMS’ signifies the possibility for accidental ignorance toward the condition. When women are led to think of their incapacitating symptoms as ‘just PMS’ they may feel that their experience is ‘normal’. The result of conflating symptoms causes many women wait to seek help until they reach their ‘breaking point’. By this time, women suffering from PMDD describe that their relationships, work and daily life have been significantly impacted.

How it impacts an individual’s life:

Gogglebox Australia’s, Isabelle Silbery, recently penned a deeply personal article recounting her feelings of desperation and frustration prior to being diagnosed with PMDD.

Detailing an upsurge in arguments with her family accompanied by bouts of worthlessness, doubt, and despondence toward exciting things in her life – Isabelle called out for greater awareness and education for women regarding their cycles and the boundaries of what should be considered ‘normal.’

It was relentless. I hated myself, I hated my partner, I hated everything.

Isabelle says that her revelatory diagnosis stemmed from her mum, fortunately, catching a radio segment on triple R discussing a newly recognised disorder that bore markedly similar symptoms to her own.

Finding a printout on her pillow, she read about PMDD and was shocked and relieved to find she ‘ticked every box.’ Paranoia, fatigue, sensitivity – experienced only between ovulation and getting her period. Suddenly, Isabelle felt empowered – she wasn’t ‘going mad’ – there were answers.

Upon seeing a new specialist (who told her undoubtedly, she was experiencing PMDD) – Isabelle recalled asking:

Her doctor, Dr Lee Mey Wong from the Jean Hailes Clinic for Women’s Health, explained that ‘women who suffer from PMDD have what’s called a ‘vulnerable brain’, meaning they may have suffered some trauma in their formative years. This vulnerability can lead the brain to be acutely sensitive to the by-product of progesterone – a hormone the body makes every cycle. This sensitivity contributes to the onset of symptoms that characterise PMDD.

In the process of learning about herself and her body, Isabelle found there was a lot more about periods, cycle phases and women’s health, in general, that she wasn’t across – prompting her to question:

Why aren’t we educated around our cycles more as young girls? Being told you get your period and to use a pad or tampon is not enough.

Isabelle’s message was simple: women are often made to feel crazy when they feel something is wrong. Yet we know ourselves better than anyone, and we’re usually right. Information is power, and we need to empower ourselves and each other to assert control over our bodies. It is time we all prioritise our health and stop our silent suffering. To do this we have to stop demonising our hormones and periods.

A UK-based journalist, Jenny Haward, also shared her story of figuring out she suffered from PMDD. For her, the early years of getting a period were characterised by some ‘mild bloating’ and an ‘off chance that [she] might shed a few tears over a not-particularly-sad film’ with 48-hours of light bleeding to follow.

But, by her 30s, this had changed. Haward describes that being someone who had never tracked their period, it took her a while to make the connection that what she had begun to term ‘the dark week’ was linked to her cycle.

‘The dark week’ would bring tingling in her extremities, bloating of her stomach and hands and what she terms the ‘PMDD hangover’ – Non-alcohol related but reminiscent of the hazy, sick feeling you get after a few too many, tinged with ‘The Fear’.

Haward describes the week before her period as charged with anxiety that pulsated through her, hyper-fixation on worries and exacerbated by insomnia – leading to fights with friends and terror toward work projects. But, as soon as her period arrived – she’d snap out of it.

Significantly, for Haward and many other women coming forward sharing their story – it took until the day she had to leave work, so ‘overwhelmed with misery and inability to function’ to call a doctor for an emergency appointment.

Haward wanted her story to reach women like herself and tell them: ‘there is help – you’re not making a fuss, or crazy or an awful person, and most importantly, you are not alone.’

PMS or PMDD?:

Lynda Pickett, the Australian Project Coordinator for ‘Vicious Cycle: Making PMDD Visible‘, explains that PMS is an average onset of physical and sometimes mild emotional symptoms and typically doesn’t cause any life disruption. On the other hand, PMDD is characterised by severe, life-impairing emotional symptoms that last 1-2 weeks before menses onset.

Recognising this difference between PMS and PMDD is crucial to understanding the significance of the disorder. While 1-2 weeks may sound manageable, when you factor in these symptoms occurring every month, every year – you can begin to get a clearer picture of the rollercoaster of emotion and life instability that sufferers face.

Symptoms:

Kin Fertility list the 11 symptoms of PMDD as the following:

- Mood changes

- Irritability or anger

- Depression

- Anxiety

- Lack of interest in things you usually enjoy

- Difficulty concentrating

- Fatigue

- Change in appetite

- Insomnia

- Feelings of being overwhelmed

- Bloating and breast soreness

Experiencing five or more of these symptoms in a life-impacting way mean that you may meet the diagnostic criteria for PMDD.

What is it? Why do we need to talk about it?

PMDD is a disorder that sits between psychiatry, gynaecology and other mimicking conditions—making getting a diagnosis a lengthy process due to the necessity to rule other possibilities out.

In Australia, the average ‘lag to diagnosis’ can take eight years.

This lag is in part due to the experience of having symptoms downplayed by doctors as ‘just PMS’. This dismissal often requires a necessary determination on the part of the individual to challenge what they are being told. Due to many doctors being unfamiliar with the condition, a referral is often necessary, or the individual has to search for answers themselves.

Lynda Pickett shared significant statistics relating to the number of people affected by PMDD:

- It is speculated that up to 90% of people living with PMDD are undiagnosed. It is not uncommon for PMDD patients to be misdiagnosed as bipolar or as having generalised anxiety or depression.

- A recent study found that 30% of respondents living with PMDD had attempted to take their life to escape their severe symptoms. A much higher percentage had experienced suicidal thoughts and self-harming behaviours.

Treatment:

Although there is no ‘cure’ for PMDD, there is a range of treatments available to help manage the symptoms.

Several medical therapies are effective, including antidepressants (SSRIs) which surveys show have provided relief to 75% of sufferers.

Oral contraceptives are also routinely prescribed to treat PMDD. Due to the pill’s interference on ovulation and the production of ovarian hormones, the pill can give greater control over the menstrual cycle and therefore reduce the severity of symptoms.

Further, many women report that additional things like reducing caffeine and alcohol intake and taking supplements such as magnesium, calcium and B6 can help. As well as making lifestyle changes in the lead up to their period in particular, such as more exercise, sleep and generally taking it easy, can make a significant difference.

Support:

Joining PMDD support groups can also give sufferers a much-needed sense of community and connection when coming to terms with their diagnosis and managing their symptoms on a day-to-day basis.

Lynda Pickett says she ‘doesn’t know where she’d be without her PMDD Peeps‘, the group name shared by her fellow PMDD community. The hashtag ‘#PMDDPeeps’ is widely used across Instagram and Twitter to connect sufferers with PMDD.

Facebook groups for individuals with PMDD, partners, post-op groups or child-free women are also widely available. These groups exist to give and receive support from people who are in the same boat.

Other great resources and groups who are bringing people with PMDD together include:

www.viciouscyclepmdd.com = a patient-led project that is focused on raising awareness and raising the standard of care for those living with PMDD.

www.iapmd.org = A global charity that offers peer support, education, research and advocacy.

www.mevpmdd.com = a PMDD symptom app.